DIFFERENT DANNY AND OTHER STORIES

10 MARCH - 14 APRIL

2022

~ Mario D’Souza

Behind the cinematic image are invisible processes of divination – bodies and

apparatus that converge to form combinations and contraptions for production.

Several practices and objects associated with cinema are often identified using

terminology only understood by those in the filmmaking fraternity. This invisibility is

both violence and possibility to those it envelopes. In Different Danny and Other

Stories, Amshu Chukki foregrounds these skills, devices, and conditions to conjure

an atmosphere that complicates labour and its relationship to the architecture of

cinema and the city.

A dupe is a stunt double for an actor – a body that is called to deliver difficult

choreography under looming danger. Being a dupe is also a call to thrill, and thereby

entertainment. Danny - the protagonist of Chukki’s film - describes a walk along a

stream and through a thicket that eventually opens up to a waterfall. In a moment of

hesitation and confusion, Danny jumps off the cliff for a shot. A sense of duty is tied

to this act (although it might of be applauded as an act of courage). The film industry

employs thousands, each hailing from across diverse social backgrounds and

skillsets, re-classifying them to uphold a system of hierarchies tied into notions such

as respect and duty. With the complete closure of filming due to the pandemic, not

being able to perform this duty left Danny in a state of anxiety. Here, a third kind of

suspended time takes over. Recollections and choreographies for the future become

devices to navigate and contend with this new time. Chukki’s camera meanders. It

captures, on one hand, the atmosphere and apparatus of cinema: men handling

equipment, cameras, rain curtains, tarp, and lights. On the other, it captures the city

in a state of interruption. Danny notes how the city itself becomes a tool for imagining

stunts; how it is the ultimate inspiration and set. Under-construction or abandoned

buildings, flyovers, factories - assets that once represented the city’s development

and/or its possible futures – become mere surfaces for choreographies with bodies.

These impulses spill out from the video into the gallery space.

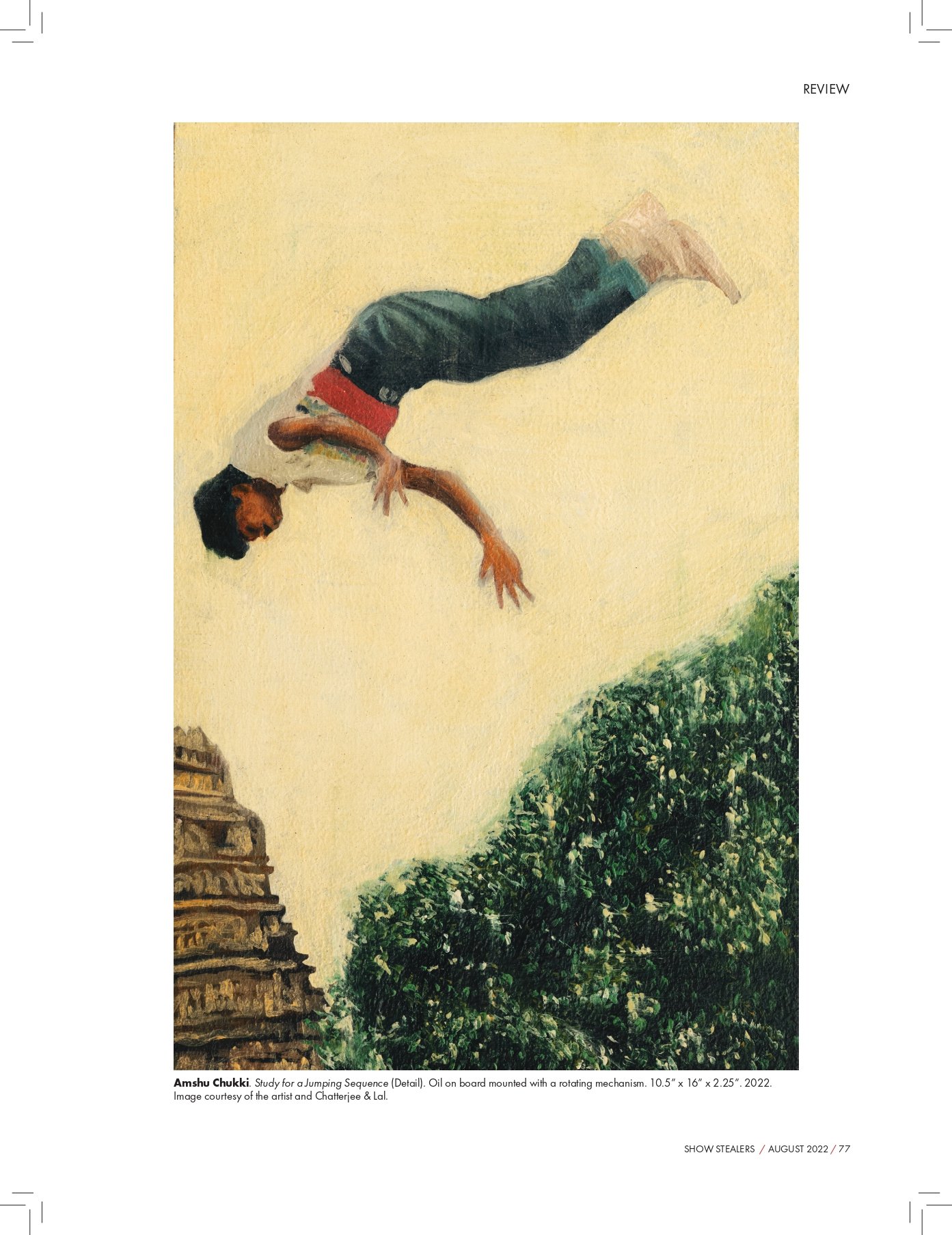

To jump, to leap in space, becomes both a device and a metaphor to physically

destabilize points of view. Like a hypnotizing act, it trains our vision to maneuver

space with the body as it turns. It takes our attention away from the imposing city and

draws us instead to its otherwise insignificant, tiny occupants. In Study for a Jumping

Sequence, Chukki toys with this proposition. We see a stationary body stretched into

a leaping curve, set into motion by a rotating surface. Close to the jump is a series of

delicate sculptures titled Recce - a term that originates from military inspection and

described the process of scouting potential shoot locations and their needs and

conditions. Here, silhouettes of bodies are layered onto wireframes of flyovers,

buildings, and pillars. The body is seemingly in motion, using a stop-motion-like

technique to suggest action.

In Shooting Mane, a two-channel video work, Chukki foregrounds the house and the

many characters it plays as a shoot location. Its permanence as home to a family is

juxtaposed against its life as an ever-changing set (a dupe). Like the body of the

stuntman, the architecture of the house also extends spatially and in terms of its

identity. Sometimes many houses exist within this one house simultaneously. As we

witness the transformation of these spaces during a production, families and film staff

talk about possession and freedoms, control and commodification, reality and

suggestions, aspirations, temporality, and the temporary. These houses and their

contents also stand as witnesses to two parallel times: the real and the cinematic.

Hours of work are reduced to a few seconds of footage and the only measure of time

and labour is the fatigue of the body and the movement of props.

States of suspension and ideas of care are represented by cords with Carabiner

hooks: safety gear also used to append and fasten. The cords recur through Chukki’s

works. In the installations Dupe, Appendage and Suspension, they extend in two

directions from jackets installed on the wall and find their termination anchored to the

floor (at one end is a building and at the other a leg, both strained and twisted like in

a leap).

In Chukki’s work - like in films - the image is first encountered in words. Vivid

descriptions surrender themselves to the imagination of each receiver. Everyone

perceives the scene distinctly in their minds, even though the settings and dialogues

are more or less the same. This is the beauty and violence of absences. The mind is

reliant on ready, processed images and seeks to consume without context, without

regard for process and labour. This delay between word and image can be read as a

suspension.

Here, props, stands, temporary sets, and stretchable bodies enmesh with desire,

demand, and danger to come to terms with the inevitability of adjustment and

change. Either through mimicking or challenging the natural, conditions such as

temperature, season, and light are either resisted or required. Through film,

installations and paintings, Chukki delves into cinematic time through and with these

‘background’ protagonists. Nonlinear, ductile, and sometimes suspended, time is

unraveled against its very source: the spectacular city.

Amshu Chukki: The Tour

Chatterjee & Lal, Mumbai

November 10 – December 23, 2017

by Zeenat Nagree

To speculate about the future is to imagine other possibilities of what the present holds and how it might progress. Such exercises of the imagination allow one’s narrative to stray from the ordinary to the unexpected, even while taking into consideration our current fears and fantasies. As they magnify and mutate, we become spectators of our own transformation, experiencing the electric thrill of contemplating what might likely never happen, while accepting that it just might. To speculate, then, is to play with the parameters of history before it comes into being.

Artists operating in the speculative mode today are working perpendicular to widespread disagreements about what constitutes fact, and its deliberate manipulation for economic and political gain. In India, for two decades now, Hindu nationalist groups have attempted to rewrite history textbooks with a view to developing a majoritarian national consciousness. Three years ago, Prime Minister Narendra Modi went on to claim that evidence of advanced scientific developments can be found in Hindu myths and epics, such as in the purported use of plastic surgery to attach the head of an elephant to the body of a deity called Ganesha. Within such circumstances, as playful as artistic speculation might be, it may also need to hold onto tools of criticality. This delicate balance between demonstrating evidence and indulging in reverie makes speculation a particularly challenging artistic device.

Last December, Indian artist Amshu Chukki presented two speculative projects in his debut solo exhibition, The Tour, at Chatterjee & Lal Gallery in Mumbai. One of the projects, which shared its title with the show, comprised a roughly 20-minute two-channel video and a series of fibreglass sculptures. In the video, a tour guide named Nagarajuna takes viewers through a deserted city without ever appearing on screen. We are tourists amidst empty buildings and shuttered shops – a rather neat and ordinary setting for an apocalypse – hearing Nagarajuna explain a circuitous chronology of events. The sea overtook the land, and then rocks fell from above; aliens used to live there and then they disappeared; the arrival of aliens caused the city’s inhabitants to forget how to speak English.

As the camera moves from the city to an airport, it becomes clear that we have been wandering through film sets all along, looking at facades that try to but never quite entirely resemble the structures they represent. In the closing sequence, the narrator proffers, “All the people who lived here watched a lot of films. They would imagine these films. Did these imaginations doom them? Or did these films lead to their doom?” With these words, the story loops back on itself. The generous pans of slightly odd yet generic architecture and design elements combined with Nagarajuna’s bizarre narrative highlight just how objects that lend verisimilitude to the cinematic image can be detached from their intended signification at whim. All editing, after all, is a form of manipulation. Alongside the video, Chukki presented fibreglass casts of rocks, hollowed out and coated with an iridescent tint on the inside.

The 26-year-old artist has been working in the speculative mode at least for the last two years now. As part of an ongoing artistic exchange between Quebec and India, Chukki was invited to Montreal’s Darling Foundry in 2015, to realize his project of researching and filming examples of utopian architecture in the city. Of these, he chose Montreal’s Biodome, originally constructed as a velodrome for the 1976 Olympics, for a roughly 12-minute video titled Mountain, les invisibles. Like The Tour, this video’s narrative takes a bizarre turn, as the Biodome’s employees – much like the tour guide – begin fabulating using the surrounding landscape as speculative prompts. We hear overlapping tales of war, an apocalypse and extraterrestrials, and through them, the strangeness of the Biodome itself is thrown into relief – an enclosed space that recreates diverse ecosystems using live animals and plants. In several frames, we also see the Biodome’s trompe l’oeil architectural details, which serve no function other than to make the dome visually coherent for the viewer. Here, the strange is contained within the ordinary; it merely requires the off-camera speakers to make it evident. Chukki thus highlights the blurry boundary between plausibility and implausibility in our daily lives, and the instrumentalization of the image in making an argument one way or another. Both The Tour and Mountain, les invisiblesrely on the awe of storytelling, showing that whether or not the image co-operates, it can be co-opted for any purpose.

Like Chukki, several young artists in India are increasingly engaging in speculation in their work. Critic and curator Nancy Adajania describes this tendency among Chukki and others like Sahej Rahal, Pallavi Paul, Rohini Devasher and Neha Choksi as “a philosophically informed approach to history that is playful in terms of its handling of material, its fusion of fictive scenarios and the evidentiary. Yet, this tendency insists on rigour and criticality, in working from a commitment to what history is for from a liberal-progressive point of view.” An exemplar of such an approach can be found in Tejal Shah’s Between the Waves, shown at documenta 13 in 2012. Shah’s post-apocalyptic world is a queer utopia, where the tasks at hand are to reconnect with a devastated, garbage-filled landscape and with the other one-horned creatures that inhabit it. They work, they dance, they express corporal desire. Owing to the explicit nature of the project, the film was only screened privately in Mumbai after being exhibited in Germany, its speculative scenarios having been deemed too offensive. What, perhaps, could be added to Adajania’s description of the speculative – and seems to be somewhat elusive in Chukki’s speculations – is Shah’s use of transgression, which lays bare limits of freedom in the present.

THE TOUR

10 NOVEMBER - 23 DECEMBER

2017

Namaste and myself Nagarajuna, I’m your tour guide.

~ Skye Arundhati Thomas

A camera trails across a deserted landscape, and we could be in any urban metropolis, emptied of its inhabitants. Our narrator, Nagarajuna, with a voice strong and clear as the sun that pours into the scene, says, “Look, now, a different atmosphere has been created here. You know what is that atmosphere?” Words disappear. Atmosphere remains.

In Amshu Chukki’s, The Tour (2017), a two-channel video installation shot in the Ramoji Film City in Hyderabad, the camera moves like a nervous, first-time player of a first-person shooter game, never quite finding a protagonist upon which to settle. The narrator, a tour guide, is a total fabulist, whose storytelling has been sharpened by years of navigating the Film City landscape. Chukki acts as provocateur: allowing the tour guide to set off on fantastical recitals – where he often speaks to us from the future. A speculation of the future is a constant theme in Chukki’s work, he asks, “How can we use collective ideations to carve out space for futures that are resilient, compelling, and beautiful?”

Chukki’s practice often investigates constructed spaces, such as the Film City, and their innate fiction-making potential. In the exhibition, Chukki deconstructs the nature of a Biodome in Montreal through several iterations: a single-channel video, with the sporadic voice-over of a tour guide; charcoal drawings on paper; and fibreglass sculptures that, with their iridescent corners, extend Chukki’s conjecture onto the sculptural plane. Chukki cites Japanese filmmaker Masao Adachi as an inspiration, in whose film A.K.A Serial Killer, a parodic voice-over (narrated by Adachi himself) explains the departure from linear story telling and asks that we focus on the fragmented, and forensic, nature of the landscape itself. Similarly, in The Tour, Chukki is determined to show us that although the film city is a fluid space, prone to alterations with each new film, it is still hyper-localised – a locality fluently narrated by its most enthusiastic inhabitant: the tour guide.

In the exhibition, we are given the fragments of a landscape: starting with the large and small fiberglass boulders. These are casts of real boulders Chukki found while in Hyderabad, characteristic of the rocky terrain of the Deccan Plateau. From a distance they look real, heavy, and, even, otherworldly. But upon closer look, the illusion dissolves easily, and instead we are pulled into the glimmers of iridescence painted onto their corners, or along their interior. Chukki uses these highlights sparingly, and hopes that we chance upon them while moving around the work. The smaller rock sculptures, if viewed head-on, appear as though flattened and two-dimensional. The addition of chrome paint intensifies the relationship between the sculptures’ pulpy interiors and the light that falls upon them. The light seems to infinitely bounce off the sculptures’ inner grooves, as though caught in its own dramatic interplay.

The drawings in the exhibition are erasures: Chukki fills up a page with dusty, flaky charcoal, before beginning a long process of wiping away, or erasing through its layers. Each drawing is achieved through a process of excavation. The artist pours over the large sheets of paper, with a toolkit of sharpened erasers, slowly carving out their forms. The drawings enact a language of liquidity: everything looks as though it may suddenly shift, or dissolve into the haze from which it emerges. Although Chukki builds enigmatic landscapes full of illusions, the illusions are not always meant to hold, or to always convince. In the accompanying film, The Mountain, Les Invisibles, while the camera is panning across the interiors of the Biodome, suddenly a wall cracks open, letting a staff member through a hidden door. Chukki is interested in the movement of people in the Biodome, staff and visitors alike, and how they are both part of the illusion, as they are privy to break it. The camera travels slowly across the plants that bloom in their entirely artificial atmosphere; in a space like this, what is real? What is fiction? It doesn’t matter.

Chukki builds a landscape in which everything is connected, and where it is difficult to see things in isolation. One work collapses into the other, or a single element repeats in unexpected ways: take for instance the choice of the lavender iridescence that peeks at us from inside the rock sculptures, where upon a closer inspection, the same lustrous tones may be found in the coin-sized film of another work, Remembering the Sea (2014). In this work, Chukki has extracted a seascape from Tarkovsky’s film Solaris (1972), a Soviet science-fiction film based on Stanislaw Lem’s novel of the same title. The extract of the film is projected onto a small piece of carved driftwood, mounted on a metal stand. The film is both magnified and minimised – the sea abstracted to a single loop of itself. The film dissolves into the grain of the wood, and film and material becoming a single unit by their juxtaposition. “When I start a work, I start with a figure. But slowly through my process, that figure is completely obscured,” Chukki explains.

Chukki takes us through chameleon-like spaces that both adapt to, and shed, the fictions to which they are introduced. It is a deconstruction of what it means to make fiction, and also the presentation of a landscape in which to do so ourselves. The cinematic experience is broken spatially, and, as viewers, it is as though we stumble into revelations about what we are shown. “All signals got disrupted,” says Nagarajuna over the scene of an empty airplane cabin, “Rocks fell from the sky, everyone disappeared in a minute. Where did they go?”

Birgid Uccia - ‘Ropewalker’s Flight’, ‘India - Maximum City’ - St.Moritz Art Masters, Chesa Planta, Zouz, St. Moritz, Switzerland, 2014.

Already in his early painterly compositions Amshu Chukki was preoccupied with films, their uneven narratives and unfamiliar visual logics. By the time he was nearing completion of his Bachelor at the art school in Baroda, video as a medium became his mainstay. ‘Ropewalkers Flight’ is a 3-part installation comprised of 2 video projections and a tribal bow. The artist shot the scene of tightrope walking himself while following a family of acrobats with his camera. In daily Indian urban life ropewalkers encroach public spaces to perform their delicate acts of balance. Amshu Chukki’s installation explores the temporality and fragility of these acts in the liminal space of fiction and reality.

Tightrope walking comes across as a stark intervention in the crowded urban space. A space of transition it allows the body to interact with the city. Following popular traditions of itinerant performers that were once common all over India, millions of children walk the financial tightrope to survive on the streets today. The act of plucking the string of the bamboo bow, made by tribal communities of Gujarat, connects this tradition with the mythologies and epics of these threatened communities. It also points to the tension and cleavage that social disparities create in Indian society. In its metaphorical sense, the phrase ‘walking a tightrope’ refers to the intricacies of balancing this precarious situation.

Sitara Chowfla - Peers 2014, KHOJ - New Delhi, India, 2014.

Having spent more than half a decade at M.S. University, Baroda first completing his B.F.A. and then his M.F.A., Amshu Chukki was well aware of Khoj and its annual Peers program through his colleagues and classmates. Chukki was at first drawn to Peers because of the opportunity it offered to experiment, and to be away from collegiate constraints, which he identified as a feeling of being “stifled by the repetitive nature of academic coursework.” Peers also held the additional appeal of interacting with a group of sharp, talented young artists from entirely different backgrounds and from various corners of the country.

Chukki’s work had mostly been an exploration of painterly work, and the bulk of his practice during his B.F.A. was dedicated to using oil paint on canvas. The subject of the artist’s work shies away from being directly representational, and instead he often chooses to paint realistic objects in an abstracted way, experimenting with focus and focal length to proffer distorted images that have a slightly disarming effect on the viewer.

The artist is a self-confessed film buff, and his adoration for the cinematic is quite apparent through his work. Still images from films made by directors of cult-popularity, such as Andrei Tarkovsky and Wong Kar Wai, often appear in his work. Curiously, the film stills that he chooses are originally framed and styled by the cinematographer to closely evoke the sensuality and emotional quality of oil paintings. By recreating these filmic images once again within a painterly schema, Chukki’s work evokes a unique layering of both reference and medium.

Eventually, Chukki’s passion for the moving image pushed him towards creating his own video-based art. While at college, the young artist experimented with interspersing his different medium-based interests, creating mixed-media installation with video and sculpture. With each work created, Amshu unveils different motifs with links to a larger narrative that he builds through his entire practice. As he claims, he is fascinated by ‘liminal spaces’ – seeking to capture the obscurity that occurs in the stillness in overlooked spaces.

As with many other artists in the group, the environment of Khirkee village captured the imagination of Amshu with a sustained ferocity. For an artist who already gravitated towards complex layering and vivid cinematic reference, the densely populated, enigmatic streets of Khirkee were a significant inspiration. Amshu’s video based installation became hinged on one visual framing – a curious composition he glimpsed while passing through a pet store on one of our early group excursions around the neighborhood. The image he made during this first visit became the keystone, which guided the rest of his installation. This comprised of manipulated filmic visions of the Khirkee masjid, the pet store, and the dense interior space of basement level tailor shops which populate the Khirkee area. Amshu played

these altered video loops onto an assemblage of old-fashioned television sets, which were then installed into the narrow environs of an elevator shaft in the Khoj building. The final presentation of his work created an unfamiliar abstraction and alienation towards spaces we would consider familiar.